Alan Larkin Painter, Printmaker, Problem-Solver

South Bend artist Alan Larkin creates design problems to solve within his own style of realism.

By Jan Wiezorek

Elysium

South Bend artist Alan Larkin asks himself questions before beginning a new artwork. Problems and solutions come to mind when he paints with oils or prints from a copper plate, creating realistic artworks of still life, nature, humanity, or mythology.

His new “wreath series” of oils, often 29-inch by 33-inch ultrarealistic canvases that feature flowery wreaths (like you might hang on your door) is contrasted with a background as flowing as water imagery or as defined and fussy as a handheld fan or geometric wallpaper.

Paper Wreath

“Generally, I work on a series,” he says, “with the simple problem: a wreath on a background. I want to activate that space using a color problem. I’m trying to devise a painting with a color idea in mind. I want the wreath section to have the greatest illusion of volume and depth, which can be a challenge when using muted values that are close together.” An example of Larkin’s color solving in his new painting Paper Wreath (left page).

Painting at his home, an Arts and Crafts masterpiece on West Washington Street in South Bend, Larkin first collects flowers from his garden or uses paper flowers (roses, for example) to investigate a problem. “I am — problem oriented,” he says. “I always look at paintings as problems in need of solutions.”

Storm Wreath

He creates a wreath and then may ask such questions as: Which colors will make the flowers dominant? How can one add depth to the composition? How could an artist add dark colors into light areas—and vice versa—to create unity? How does design contribute to unity? And he attempts to answer these questions and creative problems within the painting.

Submerged Wreath

The kinds of questions he asks, such as whether the work is coherent and unified, are at times strikingly like those his father includes in his own textbook on Gestalt psychology as a major design aesthetic, a popular influence for artists at Germany’s Bauhaus school in 1919-1933. In fact, Design: The Search for Unity (Wm. C. Brown, 1988), a book by his father Eugene Larkin, is dedicated to Alan Larkin’s artist-brother Andrew and to Alan Larkin himself, who offered his father a constructive critique of the text prior to publication. Though the book is out of print, Alan Larkin searches for used copies online so he will always have one handy.

Apotheosis

The next part of Larkin’s creative design process involves photography and adding a background using computer imaging. He may alter the photo as he completes his design. “I will photograph, take the wreath into Photoshop, and work with it extensively to enhance it. I do a lot of my designing up front,” he says. “I complete a digital image I’m happy with and use that as my template.” He believes “artists would be nuts not to use computers now” because of the design flexibility they afford. As he paints, Larkin begins to add to and subtract from the initial design. Some paintings he completes in three days; others, in six weeks, depending on the complexity of the composition.

Unlike plein air painting, where an artist may attempt to replicate the colors of the outdoors, Larkin says shapes—rectangles, triangles, circles, and more—are the foundation of his still-life compositions. He learned about them as a boy when creating tabletop Tinkertoy models of Gothic cathedrals, with a nave, flying buttress, clerestory, and other architectural features based on common shapes.

The Bird Thieves

Rivals

Another question Larkin might consider is how similar—or dissimilar—he is from his father. “We are like our parents, but we also react against them,” Larkin notes. Unlike his father, Alan Larkin bucked the trend toward abstraction that his father often took. “Dad was a great designer and a fine artist, but he couldn’t help me do the drawing that I needed to do. It was difficult to find instruction. I was convinced as a kid that people had forgotten how to paint. They didn’t have the techniques to do realistic work. I was interested from a young age in learning to draw from life,” he says. “What I saw at the time didn’t seem to relate to what John Singer Sargent might have done.”

Like his father, Alan Larkin, 71, has devoted his life to art, and his realistic still-life paintings, portraits, and prints of women, men, animals, and nature seem at times to step out of the nineteenth or early twentieth centuries. They contain vivid color and detail, perhaps reminiscent of works by N. C. Wyeth, William McGregor Paxton, or a fine magazine illustrator from the glory days of Collier’s Magazine or The Saturday Evening Post.

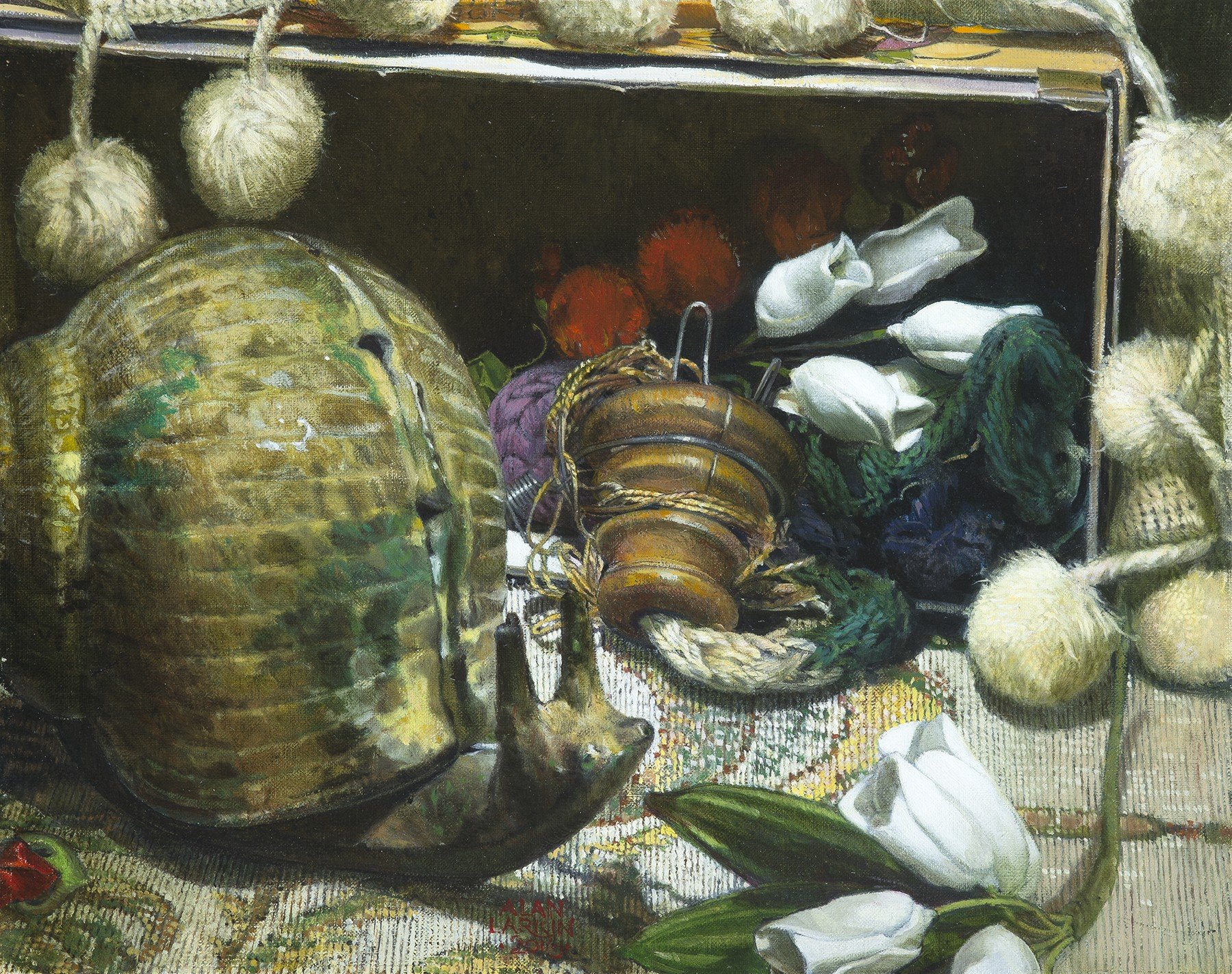

A Box Full of Notions

Story

Larkin received his formal art training at Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota, and, in 1975, earned a Bachelor’s of Art Degree in Studio Arts. In 1977, he received a Master’s of Fine Arts Degree in Printmaking from Penn State University, University Park, Pennsylvania.

He has participated in more than one hundred juried competitions and exhibitions, and his work is in the collection of the South Bend Museum of Art, which, in 2019, held an art show titled Voyage: The Art of Alan Larkin. His paintings and prints are in the collection of the Richmond (Indiana) Museum of Art, and South Shore Arts in Munster featured his paintings in Through the Looking Glass: The Work of Alan Larkin in 2015. The corporate art collection of NIPSCO also includes his work, as do the Indiana State Museum in Indianapolis, and the Fort Wayne Museum of Art.

Rose of Sharon

Teaching was important to Larkin’s father and remains so for Alan Larkin today. Eugene Larkin taught design at the University of Minnesota-St. Paul, while son Alan Larkin over nearly forty years, taught a variety of art courses—from etching, lithography, and silkscreen to book art, paper-making, figure drawing, and artistic anatomy - as an associate professor in the Department of Fine Arts at Indiana University-South Bend, retiring eleven years ago. He still teaches workshops for arts organizations throughout Indiana.

“I like teaching,” he says. “It’s useful to organize your thoughts and write them down so you can share them with others. It’s a good way to learn yourself . . . to learn from problems in the studio and rationalize your way through them.” Sometimes his art students teach him tactical ideas, such as using a roller to block out dark areas on a canvas quickly.

Historic preservation is also of interest to Larkin, who owns four properties in South Bend, including a former Studebaker mansion and, next door to his home, a house he rents to visitors through Airbnb. “Mostly I consider myself to have been absurdly lucky to have had a life in art,” says Larkin.

After the Ball

At the rental house he has a common space on the first floor, with gallery-style lighting, where several of his father’s large, black-and-white abstract prints are on display. Now, he is cataloging his father’s artistic output and is preparing to sell the lithographic prints online. Larkin’s father died in 2010.

Lost in the Wreath Garden

While his “very supportive” partner Amanda Ward is baking bread inside their home, Larkin strolls out in the yard behind his Washington Street house, where he has lived since 1985. A small tree is being propped up, a woodshop with tools is open, a red garden gate shines in sunlight, and a printmaking studio out back houses his father’s press, as well as counters and tables for creating prints from copper plates. He built a cabinet that diffuses a ground onto the plates so they can be prepared properly before printing. He also devised a metal arm that holds his swinging water faucet, enabling him, when he desires it, to focus a consistent flow of water onto his plates and other materials. Again, Larkin is a man questioning and seeking handy solutions.

The Flower Arrangement

When Larkin paints, he says he does it for himself. But he knows the realities of the art market. He would be happy to receive a plumber’s hourly wage for the time he spends on each artwork. His works range in price from about $500 to $10,000 or more, while his black-and-white prints begin at about $250.

Larkin advises artists to network with artists and buyers—and to have both a gallery and a social-media presence so the public can see their work. And he suggests that students (and everyone) improve upon their talents by reading. “We should all be reading a lot and not assume that our talent is a discreet entity that is either there or not,” he adds. “We should be working to broaden our minds all the time.”

Another mind-broadening experience may be simply sitting before a Larkin painting and observing a thrill of color over your eyes. What one sees is meditative, stunning in its depth and illusions: Certainly, a needed solution to the many problems of daily anxiety at hand.