Wild Summertime by Colleen Newquist

“Summer afternoon—summer afternoon; to me those have always been the two most beautiful words in the English language.” — Henry James

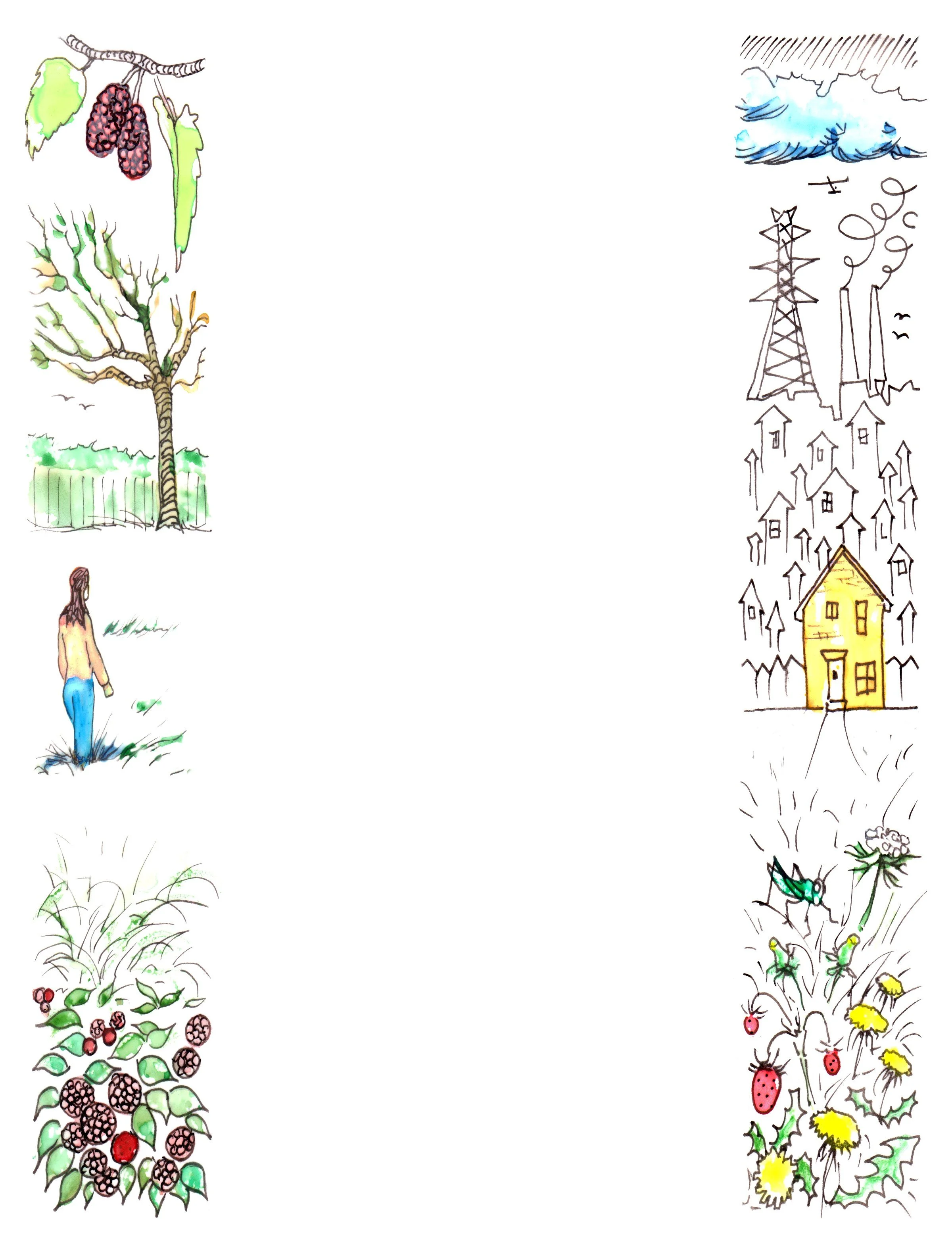

Mulberries rain down on our gravel driveway and deck, making splotchy muck that we track into the house. The mulberry tree sprouts at the edge of our lot, where the driveway meets the neighbor’s ramshackle wood fence. It’s messy, but the birds love it, so we let it be.

I pause from sweeping the deck to grab a berry from a limb. It has a mild flavor, slightly sweet. If I could figure out an easy way to harvest them (“Just put a tarp out to catch them,” one friend said), I might try making something—pie? sorbet? smoothie? Mulberries are reportedly chock full of nutrients, so it seems a shame to let them go to waste. Plus there’s something about wild berries, a gift from nature, free for the taking, that makes eating them so satisfying.

Growing up in a blue-collar south suburb of Chicago, our modest yellow brick house bordered an open field spanning several acres that separated our neighborhood from another. In summer the field was full of wild strawberries. My sisters and I would pick the tiny tart berries, smaller than a marble, douse bowlfuls with swirls of sugar, and perch on the front porch steps to devour them, our fingers turning red and sticky.

One summer when I was about 10, I had the idea that I would pick strawberries and sell them. One morning I took my bucket out to the field where I lasted maybe 10 minutes amid the scratchy weeds in the baking sun, the air buzzing with insects, before deciding my time was better spent in the cool basement drawing, or lounging in the limbs of our maple tree, reading a Nancy Drew mystery.

Another day I discovered that a large clump of ugly bushes in the field, untamed branches clustered around chunks of broken concrete, bore luscious dark berries—wild blackberries, or perhaps black raspberries, warmed by the sun and intensely sweet. My fingers stained purple as I gleefully popped berry after berry into my mouth, delighted by my discovery—until I discovered I wasn’t the only one who loved them. Ants were crawling up my jeans at a furious pace. With literal ants in my pants, I screamed all the way home, shedding my clothes the instant I burst through the back door.

Traumatic encounters with nature aside—I also recall breaking into a run when a cloud of grasshoppers flicked against my face and arms one late summer afternoon—I miss that field.

It was where I learned to love the cool mustiness of clay earth, sitting shoulder to shoulder in a dark underground fort dug out by neighborhood boys and topped with warped plywood. The field is where I smoked my first cigarette, when I was 11 (even crazier, I smoked it with an 8-year-old friend).

Lightning bugs drifted in the summer night sky while at one end of the field—an image that seems surreal to me now—movies floated on the giant screen of the Sauk Trail Drive-in, faint strains of soundtracks sometimes carrying on the breeze.

I often wondered what it would be like to have houses there, other families and kids, streets that connected us to the neighborhood beyond. The summer before I went to college, the drive-in closed, and the bulldozers came. They paved paradise and put in some perfectly nice brick homes, with perfectly nice lawns.

by JD Moffitt to see more of Moffitt’s art click on link below.

Three Oaks, Michigan, Colleen Newquist is the writer, editor, illustrator, and cook behind “Stop and Smell the Butter.” Learn more about Colleen at panoplymichiana.com or cnewquist.magcloud.com. Read more about Newquist by linking below.